Welcome to one of the most important, challenging and fascinating concepts of JavaScript — Objects. As the saying goes:

In JavaScript, objects are king. Almost everything is an object or acts like an object. If you understand objects, you understand JavaScript.

In the previous article we discussed about primitive data types and it was mentioned that some behavior of primitives is different for objects. Let’s see how they are different by starting this exciting journey together and reach enlightening in understanding JavaScript objects :).

General description

If primitive values are immutable (cannot be changed), objects are, using complex deduction techniques, the other side of the coin. Namely they are: —?

What is the opposite of the term immutable? It is mutable. And so are objects. This means that their values actually can be changed without throwing them away.

Also, in constrast to primitive values, objects hold complex data. They are containers of different types of data, including even other objects. An objects is a basic data structures in JavaScript.

There are two ways to define a brand new object in JavaScript:

- Object literal definition.

- Definition using the

Objectconstructor.

// 1. The object literal definition

var object1 = {}; // {}

// 2. Defining using the `Object` constructor

var object2 = new Object(); // {}

Both these methods create an empty object {}. If to compare these, we will get:

object1 == object2; // false

Wait, what? How come they are different if they are both empty objects?

This has to do with the way object variables are stored in JavaScript.

Storing an object

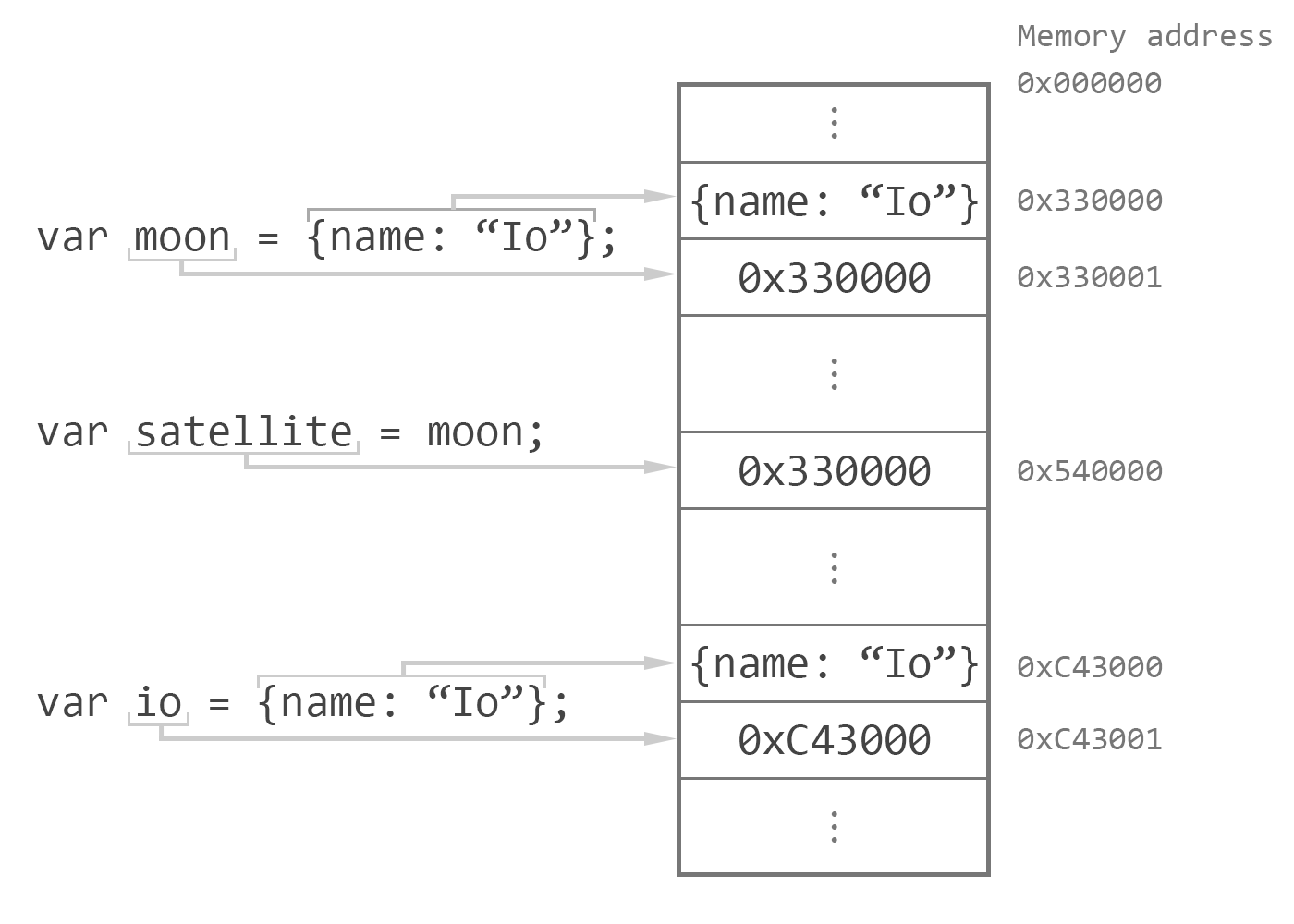

In JavaScript, objects are stored by reference. This means that a variable to which we have assigned an object actually does not hold that object in it. What it holds is just a reference, a pointer to that object in the memory. This has important and very interesting implications when programming in JavaScript, which we will address in the following chapters.

When you define an object, it is stored in memory, but the variable to which you assign that object stores not the object itself, but the address of that object in memory. Therefore it is said that objects in JavaScript are stored by reference. Then, when you assign the value of moon to the newly created satellite, a copy of its value is created and assigned to satellite. But because these values point to the same memory address, modifications to any of these variables will result in changing the same object. Then, even if you create another object with the same data as an existing one, that object is being stored in another location in memory and the address of that location is assigned to the variable io. Therefore, if you will compare io with moon, you will get false, as 0x330000 does not equal 0xC43000.

In contrast, privitives are stored by value, which means that the variable holds the actual value that we have assigned to it.

So, even if we have this comparison: {} == {}, the result will be false, because these are two different objects. When you write the first empty object, it is created and stored in memory under one address and then the second object is created and stored in memory under another address. And since these addresses are different, the equality returns false.

Comparing pens and houses

If this still seems unclear, consider comparisons in the real world. When comparing by value, you are comparing the actual things.

For instance if you compare 'pen' == 'pen', you compare the actual pens. You have two pens and check whether they are the same.

On the other hand, when comparing by reference, you compare by an address. If you have:

var house1 = {rooms: 4, color: 'orange', bathrooms: 2, sqMeters: 140};

var house2 = {rooms: 4, color: 'orange', bathrooms: 2, sqMeters: 140};

then when comparing house1 == house2 (or {} == {}, it does not matter) you compare their addresses. And even if the houses are identical, they are located at different addresses, therefore they will not be equal.

Object properties

As mentioned earlier, objects are “data structures” in JavaScript. We can store different data in them using key-value pairs.

var solarSystem = {

numberOfPlanets: 8, // sorry, Pluto!

inhabitedPlanet: 'Earth',

civilizationOnMars: null,

sendGreetingToAliens: function () { ... }

};

solarSystem.biggestPlanet = 'Jupiter';

A key is an identifier by which we can access the value related to that key. Keys are also called object properties. You can define object properties when you define the object using object literal notation or you can add them later. In case you add object properties when defining the object itself, you add them using key: value pairs by means of a column. However, when you add/change a property on an existing object, you use the = assignment operator.

Object properties are of type string, but you can define them using other types. In that case, they will automatically be converted to strings (we will talk about type conversions in the next sections of this chapter).

var object = {};

object[2] = 'a'; // the 2 is transformed into the '2' string

object['2'] = 'z'; // the '2' property overwrites the 'a' value with 'z'

console.log(object[2]); // 'z'

console.log(object['2']); // 'z'

On the other hand, object values can be of any type. In the example above we have numbers, strings, null, functions, but there can be actually any type that is available in JavaScript, even other objects.

Accessing object properties

There are two methods to access object properties: using square brackets and using dot notation.

// Access value using square brackets

solarSystem['numberOfPlanets']; // 8

solarSystem['biggestPlanet']; // 'Jupiter'

// Access using dot notation

solarSystem.inhabitedPlanet; // 'Earth'

There is no difference between these ways of accessing values and you can use whatever you like more. There is, however, a scenario where you can use only one and not the other. As object properties are strings, we should be able to easily define "the star in the center" string as an object property. And we can do this, but only using the square brackets notation.

solarSystem['the star in the center'] = 'Sun';

Another advantage of square brackets notation is that you can set dynamic object properties on an object. Suppose you have a variable that holds the key name you want to set on an object.

var saturn = {

nrOfSatellites: 62, // as of 2016

hasRings: true

};

var property = 'differentPlanet';

solarSystem[property] = saturn;

In the above example we defined an object property based on a variable and the value of that property is an object. Thus, we can have objects in objects in objects and so on, having nested structures of data.

Check if a property exists

In order to check for existence of a property, there is a special in operator. Its syntax is 'property' in object and it returns a boolean.

'differentPlanet' in solarSystem; // true, the key exists

'aliens' in solarSystem; // false, no such key

Non-existing properties

In case we do not check for property existence and simply access a property that does not exist, it will simply return undefined as its value.

solarSystem.pluto; // undefined

This does not create any key inside the object and does not throw any error. Simply put, JavaScript tells you that the value associated with the requested key does not exist.

Remove a property

To delete a property, use the delete keyword and indicate the property you want to delete.

delete solarSystem.saturn;

delete solarSystem['inhabitedPlanet']; // Bye-bye, humanity!

Deletion also works using the dot notation or square brackets. When deleting, you remove the key from the object and the associated value with it.

Object variables as references

We talked above about object variables holding a reference rather than the object itself, but what this actually means?

Let us take a simple example.

var peter = {

dressingStyle: 'casual',

musicPreference: 'pop'

};

var mothersSon = peter;

var janesBoyfriend = peter;

// Peter's mother wants all the best for her son.

mothersSon.dressingStyle = 'business';

mothersSon.musicPreference = 'classic';

// Peter's girlfriend, Jane, wants him to look like a rockstar.

janesBoyfriend.dressingStyle = 'rock';

janesBoyfriend.musicPreference = 'rock';

console.log(peter.musicPreference); // ?

console.log(mothersSon.musicPreference); // ?

console.log(janesBoyfriend.musicPreference); // ?

When talking about primitives, you saw that when referring to a value made a copy of it. How do you think, what will output each console.log statement in the case of our objects?

We have Peter that is an object (well, he is a human, but in JavaScript he is an object. I’ve talked to Peter, he is ok with that). Peter is a son and a boyfriend at the same time. Because Peter is an object, the variables mothersSon, janesBoyfriend and even peter himself are references to the actual object that contains two properties that define Peter.

So, when we wrote var mothersSon = peter, JavaScript copied the reference of the peter variable to the mothersSon variable and not its value, as it does with primitives.

What we have in the end is a single object and three references pointing to it. Thus, when modifying the mothersSon.dressingStyle property, we modify the object to which mothersSon points. Then, when we modify the janesBoyfriend.dressingStyle property, we modify the object to which janesBoyfriend points, which is the same object as mothersSon points! Therefore, the console.log statements will all display the same thing.

console.log(peter.musicPreference); // 'rock'

console.log(mothersSon.musicPreference); // 'rock'

console.log(janesBoyfriend.musicPreference); // 'rock'

In conclusion

We just scratched the surface of what objects are in JavaScript. There are many more awesome stuff you can do with objects as you will see in the following chapters.

Arrays

Arrays in JavaScript are regular objects used to represent lists of different values.

typeof []; // 'object'

typeof {}; // 'object'

But why is this happening? The thing is that an array is a specific instance of an object that has additional methods and all its keys are integers.

Defining an array

There are two ways to define an array in JavaScript:

- Literal definition.

- Definition using the

Arrayconstructor.

// 1. The array literal definition

var array1 = []; // []

// 2. Defining using the `Array` constructor

var array2 = new Array(); // []

As arrays are objects, remember that they are stored as references. Therefore [] == [] will be false, because the references of these two arrays are different.

Array values

As mentioned earlier, arrays are special instances ob objects. This means that arrays can hold any type of data as their list elements.

// You can defined it in one row

var regularArray = [1, 'a', true, {b: '23'}, [1, 2, 'x'], null, undefined];

// Or each element on a separate row to increase readability

var readableArray = [

1,

'a',

true,

{b: '23'},

[1, 2, 'x'],

null,

undefined

];

Array keys

The next similarity of arrays to objects was mentioned to be integer keys. Therefore, we should be able to access array values by integer keys. But before doing that, first you need to know that these keys are nothing else than element positions in the array.

// 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 <= index

var numbers = [4, 9, 1, 4, 3, 8];

In JavaScript, arrays are zero-indexed, which means that the first element of an array is at index 0. Thus, in order to access an array’s value, we do so using square brackets and the index at which we would like to get the value.

console.log(numbers[0]); // 4

console.log(numbers[2]); // 1

An observant reader might ask (him/her)self what would happen when accessing an index that does not exist in the array? Well, similarly with objects, the value will be undefined.

console.log(numbers[12]); // undefined

And yet, they are different

“Enough similarities! Show us the differences!” hear I nobody screaming. Ok, let’s see how arrays are different from objects.

The first difference of this kind is related to array indexes. In objects, adding a new property simply adds that property and the associated value to the object. In arrays this process is similar

var arr = [1, 2];

arr[2] = 3;

console.log(arr); // [1, 2, 3]

unless you want to add an index that is bigger than the array’s length.

var arr = [1, 2];

arr[5] = 6;

console.log(arr); // [1, 2, undefined, undefined, undefined, 6];

As arrays are list-like objects, they need to preserve this list-like behavior. This means that whenever you explicitly try to set the value at an index that is “out of range”, JavaScript fill automatically fill in the missing elements with the undefined value so that you still have a list.

“Show me the length of your array”

Unlike objects, arrays have a special length property that returns the length of the array.

var continents = [

'Africa',

'Antarctica',

'Asia',

'Australia',

'Europe',

'North America',

'South America'

];

console.log(continents.length); // 7

In order to add an element to the end of the list, we can use the .length property to obtain it.

continents[continents.length] = 'Atlantida';

Note that we don’t add 1 to the array length, as the index starts at 0, therefore the last element in an array of seven elements is 6, giving us the next position where to add the element to be at index 7 (which is exactly the length of the array).

You can also modify the length property, thus affecting the shape of the array.

var arr = [1, 2, 3];

arr.length = 5;

console.log(arr); // [1, 2, 3, undefined, undefined];

arr.length = 2;

console.log(arr); // [1, 2]

Setting an array’s length to zero is a nifty way to empty that array altogether in just one line of code.

arr.length = 0;

console.log(arr); // []

More operations with arrays

Arrays have several built-in methods that provide the possibility to make nifty operations on themselves, or their elements.

Manipulating with array elements

As in real life, lists are rarely static. We constantly need to add some things and remove other things from our lists. Therefore, arrays have some methods that gives you the possibility to operate with its elements easier.

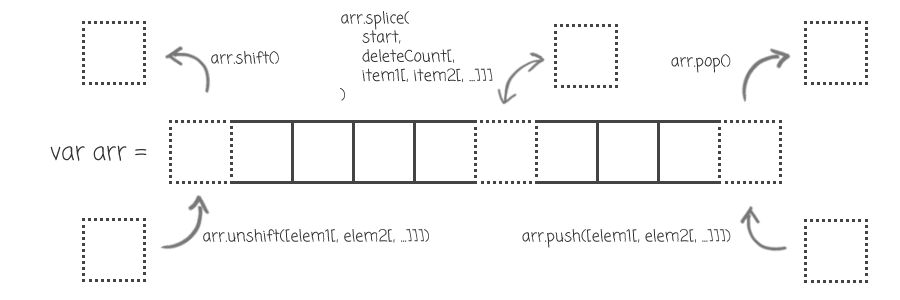

arr.push([element1[, …[, elementN]]])

The .push(elem) method adds the specified element(s) to the end of the array.

var species = ['Humans', 'Dragons', 'Elves'];

species.push('Martians');

console.log(species); // ['Humans', 'Dragons', 'Elves', 'Martians'];

arr.pop()

The .pop() method removes the last element from the array and returns that element.

var species = ['Humans', 'Dragons', 'Elves'];

var lastSpecies = species.pop();

console.log(lastSpecies); // 'Elves'

console.log(species); // ['Humans', 'Dragons'];

arr.unshift([element1[, …[, elementN]]])

Similartly to the .push() method, adds the specified element(s) to the beginning of the array.

var species = ['Humans', 'Dragons', 'Elves'];

species.unshift('Zergs');

console.log(species); // ['Zergs', 'Humans', 'Dragons', 'Elves'];

arr.shift()

Similarly to the .pop() method, removes the first element in the array and returns that element.

var species = ['Humans', 'Dragons', 'Elves'];

var ourSpecies = species.shift();

console.log(ourSpecies); // 'Humans'

console.log(species); // ['Dragons', 'Elves'];

arr.splice(start, deleteCount[, item1[, item2[, …]]])

Splice method is used when you want to insert/delete some elements from inside an array and return those elements. The start and deleteCount parameters are mandatory, and the item parameters are optional.

// Remove two elements from inside the array

var species = ['Humans', 'Dragons', 'Elves', 'Zergs'];

var removed = species.splice(1, 2); // Start at index 1 and remove 2 elements.

console.log(species); // ['Humans', 'Zergs']

console.log(removed); // ['Dragons', 'Elves']

// Add two elements inside the array

var species = ['Humans', 'Dragons', 'Zergs'];

species.splice(1, 0, 'Martians', 'Orcs'); // Start at 1, remove 0, add 2

console.log(species); // ['Humans', 'Martians', 'Orcs', 'Dragons', 'Zergs'];

// Add and remove at the same time

var species = ['Humans', 'Dragons', 'Elves', 'Zergs'];

var removed = species.splice(2, 1, 'Martians', 'Orcs'); // Start at 2, remove 1, add 2

console.log(species); // ['Humans', 'Dragons', 'Martians', 'Orcs', 'Zergs'];

console.log(removed); // ['Elves']

Copying parts of arrays

Sometimes you just need to copy a part of an array, or even a whole array. For this operation there exists the .slice([begin[, end]]) method. Note that this method doesn’t modify the original array, but creates a copy of it with the corresponding elements.

If to call it with no parameters, it will return a copy of the whole array.

var people = ['John', 'Jane', 'Mary'];

var clones = people.slice();

console.log(people); // ['John', 'Jane', 'Mary']

console.log(clones); // ['John', 'Jane', 'Mary']

people == clones; // false, these are different arrays

If to call it with one parameter, it will return a copy of the array starting at that index.

var people = ['John', 'Jane', 'Mary'];

var women = people.slice(1); // slice from the first element

console.log(people); // ['John', 'Jane', 'Mary']

console.log(women); // ['Jane', 'Mary']

Finally, if to call it with two parameters, it will return a new array with the elements between these indexes, including the element at the index of the first parameter and excluding the index of the second parameter.

var people = ['John', 'Jane', 'Mary'];

var startsWithJ = people.slice(0, 2);

console.log(people); // ['John', 'Jane', 'Mary']

console.log(startsWithJ); // ['John', 'Jane']

There are other methods available on arrays, but we’ll discuss them in the following chapters.

Function

Generally speaking, a function is a subprogram that can be called by external or internal (in case of recursion) code to the function. You can pass some values to the function and it will return a single value.

Believe it or not, but functions are also objects in JavaScript! These are special objects that can be called by means of () parenthesis after the function.

In order to define a function and assign it to a variable, you need to use the function keyword.

var myFunc = function () { /* function body here */ };

// Calling the function.

myFunc();

We won’t dive in details here, as functions deserve a hero of their own, but we’ll address some fundamental concepts as functions are also objects in JavaScript.

Defining a function

You can define a function in three possible ways:

- Using a function expression.

- Using a function declaration.

- Using the

Functionconstructor.

Let’s take them one by one.

Defining a function using function expressions

A function expression is defining a function within an expression. We have already defined a function using function expression in the previous example.

var bigBang = function () {

// explode the Universe here

};

Defining a function using function declaration

When using function declaration, we define a function using the function keyword right from the beginning of the line and we don’t assign it to any variable.

function bigBang () {

// explode the Universe here

};

Defining a function using the Function constructor

Finally, you can define a function using the Function constructor, by providing it the arguments (if any) and the function body.

var bigBang = new Function('// function body here');

Note that you won’t use this method as frequent as the first two. Just know that there are three ways to define a function in JavaScript.

Function anatomy

A function in JavaScript has the following syntax:

function name([param[, param[, ... param]]]) {

statements

}

Therefore, a function has:

- a name, which can be any name that is a valid variable name (see variable naming rules earlier in this chapter)

- parameters, which represent the names of the arguments that are passed to the function at calling

- statements, which comprise the body of the function; these can be any valid code in JavaScript, even other functions!

Calling a function

When calling a function, several things happen. Let’s consider the following example.

function sayHello ( name, person ) {

var greeting = 'Hello, ';

name = name + '!';

person.saidHello = true;

return greeting + name;

}

var john = {

name: 'John',

age: 42,

saidHello: false

};

var personToGreet = 'Tim';

var greeting = sayHello(personToGreet, john);

console.log(greeting); // 'Hello, Tim!'

console.log(personToGreet); // 'Tim'

console.log(john); // { name: 'John', age: 42, saidHello: true }

Can you explain the results? Think about it for a moment.

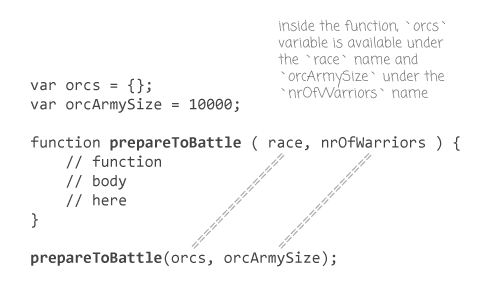

When we call a function with some parameters, these parameters are mapped to the function’s argument names in the definition block of the function and are available in the function body under those names.

One important thing to remember here is that primitives are passed by value, whereas objects are passed by reference.

This means that whenever you call a function with a primitive as a parameter, it gets copied and the copy is passed in the function’s body and when you pass an object (array, function, etc. — these are all objects), no copy is created and the reference of that object is passed.

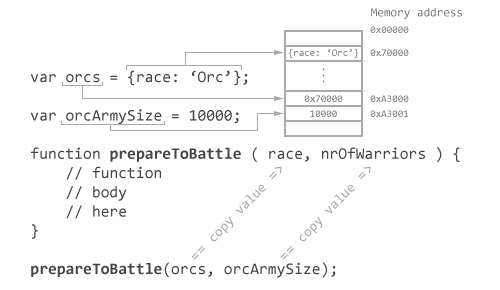

As you see from the image above, both variables get copied. The difference is that for primitives the value itself is copied (10000), whereas for the object the reference is copied. So, when the value of the orcs variable (which is a reference to the {race: 'Orc'} object) is copied, the function receives a copy of the memory address where the {race: 'Orc'} is located.

Therefore, when the function operates with the nrOfWarriors argument, which is a primitive value, it operates with 10000, which is a copy of the 10000 from the orcArmySize variable. And when it operates with the race argument, it operates with the copy of the reference to the {race: 'Orc'} object, but because the references of the race and orcs are the same, they both point to the same object in memory and any modification made by either of these variables will modify the same object.

Wrapping up variable types

These are the data types in JavaScript. As you saw, all these types have different characteristics and specifications, which you need to know. But do not be afraid! As I wrote in why to learn programming? the basic programming concepts are not hard to grasp. It’s too much information that makes you feel overwhelmed, so take courage!

Let’s make a short recap.

These are the data types in JavaScript:

- Number

- String

- Boolean

- Undefined

- Object

- Function

Primitive values are those that are not an object:

- Number

- String

- Boolean

- Undefined

- Null

Remember that primitives are stored by value.

Objects are stored and passed by reference. There are many types of built-in objects in JavaScript:

- Object

- Array

- Function

- Date (we’ll talk about dates later)

Functions are objects that can be called. When calling a function, the parameters that you pass to the function are mapped to the arguments in the function definition block.

The “unpredictability” of Master of Variables

Although Master of Variables does a great job in creating all these variables of different data types that each has its own behavior, he doesn’t care and doesn’t pay proper attention to their “appearance.” Let’s take a specific example to help us understand what I mean.

Suppose you have this variable declaration: var planet;

What can we say about it? Can we say what type of data will it hold? Can we say that it will be an object? Or a string? Or an array? No. It to make an analogy of variables as boxes, all boxes created by the Master of Variables look the same. You can’t tell what a box has inside it until you open it and check its content. So it is with JavaScript interpreter. Whenever an operation should be made on a variable, it should be checked for the type of data it holds to see whether the operation can, or cannot be performed. This checking requires time and therefore slows down the speed of execution (well, we still can’t see it impact, as computers are really fast).

Conclusion

This was a relatively short description of the Master of Variables. You will keep meeting him throughout your journey of mastering JavaScript, as variables are indispensable to any program that you write. There are still things that you will learn later on, even about the variables. But for now, you need to process what you’ve already learned so that your knowledge stays strong.

I would highly suggest you take the quiz on variables once more to check your progress and rehearse the learned material.